Historical Materials

Will Fenton

Waged in broadsides, engravings, pamphlets, political cartoons, and correspondence, the debate about the Conestoga massacres ensnared some of Pennsylvania’s most preeminent statesmen, including Benjamin Franklin, Governor John Penn, and Hugh Williamson, who would later sign the U.S. Constitution. At stake was much more than the conduct of the Paxton murderers. Pamphleteers used the debate over the conduct of the Paxtons to stake claims about peace and settlement, race and ethnicity, masculinity and civility, and religious association in pre-Revolutionary Pennsylvania.

The following primary source materials are drawn from numerous archives, including the Free Library of Philadelphia, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Library Company of Philadelphia, Moravian Archives of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Pennsylvania State Archives. Many more materials are freely available on Digital Paxton.

Beginnings

The belt of wampum delivered by the Indians to William Penn at the “Great Treaty” (Philadelphia, 1857). Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Reciprocity in treaty-making was enacted through the exchange of wampum made from shells and leather. The Delaware Indians gave this belt of wampum to William Penn at the signing of the Treaty of Shackamaxon in 1682. The scene would later be mythologized in Benjamin West’s Penn’s Treaty with the Indians.

Benjamin West, The Indians Giving a Talk to Colonel Bouquet (Philadelphia, 1766). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Benjamin West’s engraving features several aspects of treaty-making, including the recording of minutes (the scribe takes notes) and the exchange of wampum (held by the chief).

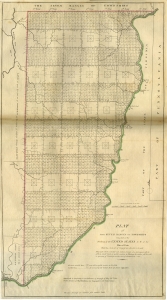

Jacob Taylor, Survey (Lancaster, 1717). Pennsylvania State Archives.

In the late-1600s, approximately 200 Susquehannocks settled on 16,000 acres restricted from colonial settlement. William Penn reportedly visited this group, then known as the Conestogas, on his second visit to Pennsylvania in 1701. This 1717 survey of “Conestoga Manor” identifies “Indiantown” immediately north of John Cartledge’s 300-acre tract.

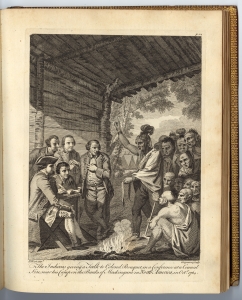

Daniel Paterson, Cantonment of His Majesty’s Forces in N. America (New York, 1766). Library of Congress.

Following the Treaty of Paris and the end of the Seven Years’ War, the British government issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which largely affirmed the territorial boundaries of the Treaty of Easton (1758). This map reflects those boundaries, designating the trans-Appalachian west “Reserved for the Indians.”

Origins of Discontent

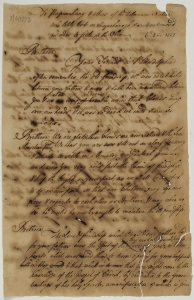

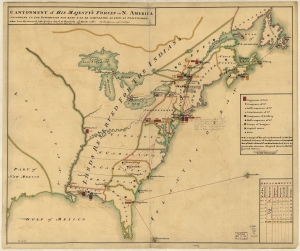

John Forbes, Letter to Israel Pemberton, (Shippensbourg, August 18, 1758). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections.

During the Seven Years’ War, Quakers played a central diplomatic role by organizing the Friendly Association, a non-governmental organization that laid the groundwork for the Treaty of Easton in 1758. Friendly Association correspondence reveals the political sensitivity of diplomacy.

“I need not tell you that a Jealousy of the Quakers grasping at power, has perhaps taken place in some people’s minds; you have now a very critical time of showing that you are actuated only by the [public] good and the preservation of those provinces.”

Israel Pemberton, Letter to Charles Read (Philadelphia, September 10, 1758). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections.

“[T]he success of the business depends much on setting out right & our Governor has neither inclination nor judgement to act, as ye occasion requires & would I believe pay more regard to a hint from a Brother [Governor] than to either [persuasions] or remonstrances from his Subjects.”

John Forbes, Letter to Israel Pemberton (Philadelphia, January 15, 1759). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections.

“I should be very sorry that you persuaded me to Do any thing that could give Umbrage to the province or provincial Commissioners by giving protections for carrying […] your goods. [Though] I cannot but highly applaud your Zeal for the service.”

[James Claypoole], Franklin and the Quakers (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Dealings with the Quakers complicated Benjamin Franklin’s political career. Franklin appears in the foreground of this etching, holding a sack labeled “Pennsylvania money.” To the left, the prominent Quaker merchant Abel James distributes tomahawks from a barrel labeled “I.P.”

The Massacres

David Henderson, Account of the Indian Murders (Lancaster, December 27, 1763). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections.

The first accounts of the Paxton murders published between December 1763 and January 1764 did not look favorably upon the Paxtons. In a letter written after the attack on the Lancaster workhouse but before the march to Philadelphia, David Henderson emphasizes the injustice of the Paxton murders.

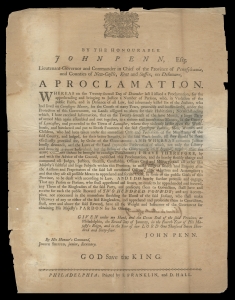

John Penn. Proclamation (Philadelphia, January 2, 1764). Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Governor Penn calls for the immediate arrest of the Paxton murderers in this proclamation. This broadside reflects the governor’s second condemnatory proclamation, the first printed on December 22, 1763, after their massacre at Conestoga Indiantown but before their attack on the Lancaster jailhouse.

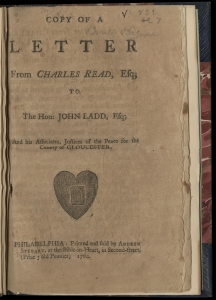

Charles Read, Copy of a Letter from Charles Read (Philadelphia, 1764). Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

This early account the Conestoga massacres anticipates arguments that Franklin popularizes with Narrative of the Late Massacres. Read presents the Paxtons as the real savages, murderers who should suffer punishment under the law. He holds that the Conestogas are subjects of the crown and entitled to security, an argument less grounded in ethics than economics.

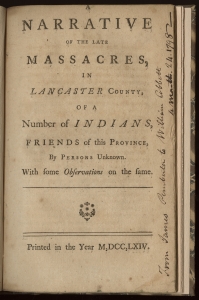

Benjamin Franklin. Narrative of the Late Massacres (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Benjamin Franklin’s influential pamphlet created a template for subsequent Paxton critique. He emphasizes the need for law and order and also personalizes the Susquehannock by using their

English names, describing familial relationships, and providing detailed accounts of slaughters. Notably, Franklin condemns the Scotch-Irish frontiersmen as “CHRISTIAN WHITE SAVAGES.”

[Anonymous], A Serious Address (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Published contemporaneously with Narrative of the Late Massacres, this pamphlet provides the first insinuations of Paxton apology. The author complains of “too general Approbation” of

the killings, despite their being “contrary to the Laws of Nations.” The pamphlet’s appearance of impartiality earned it significant popularity – A Serious Address was republished in four editions.

The Public Debate

[Anonymous], Petition by the Inhabitants of Lancaster County (Lancaster, 1764). Moravian Archives of Bethlehem.

This letter may have served as a draft of the Paxton leaders’ Remonstrance. Notably, Petition by the Inhabitants of Lancaster County only raises the problem of representation as a means to raise the concern that settlers might be tried in Philadelphia courts, rather than by their peers in the borderlands.

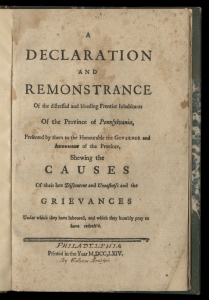

Matthew Smith, Declaration and Remonstrance (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

In exchange for disbanding at Germantown, Paxton leaders secured the right to broadcast their grievances in Declaration and Remonstrance. Their representative, Matthew Smith, read the essay as early as February 15, just a week after the marchers arrived in Germantown. Though written in haste, Smith’s grievances galvanized sympathizers who distrusted the friendly relations of Quakers and Susquehannocks, and suspected that leaders intentionally withheld support from borderland settlers. The syntactical repetition of “falsely pretended Friends” (the Susquehannocks) and “falsely pretended Indian Friends” (Quakers) served to conflate Friendly Indian with Indian Friend.

[Anonymous], Apology of the Paxton Volunteers (Philadelphia, 1764). Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

This unpublished, anonymous manuscript added visceral depictions of frontier warfare to Smith’s account. In place of scenes of violence against the Conestogas (as in Franklin’s Narrative of the Late Massacres), the volunteers emphasize the mangled bodies of settlers. Whereas Declaration and Remonstrance advocated for changes in settlement policies, Apology of the Paxton Volunteers sought the vindication of the Paxtons.

The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, The Address of the People Called Quakers (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

In this letter to the governor, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting warned the Smith pamphlet would agitate “the inconsiderate Part of the People” against the Society. Those fears proved well-founded as Paxton apologists conflated Quakers with the warring Indians that they claimed had precipitated the murders.

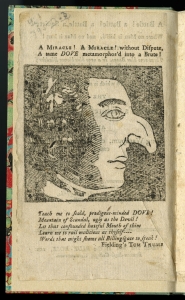

David James Dove, A Battle a Squirt; Where No Man is Kill’d, and No Man is Hurt! (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

This pro-Paxton pamphlet was published anonymously, but later attributed to David James Dove, the infamous satirist, Paxton sympathizer, and headmaster of the Germantown Academy.

(The printer included an unflattering engraving of the doctor.) Dove counters A Serious Address by mocking Friends’ superficial adherence to the peace testimony. He describes the Paxtons, meanwhile, as the “worthy bleeding Men of Paxton,” who acted to prevent Indian treachery.

James Claypoole, An Indian Squaw King Wampum Spies (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia

In this pro-Paxton political cartoon, likely intended to accompany A Battle a Squirt; Where No Man is Kill’d, and No Man is Hurt!, a Quaker merchant identifiable as Israel Pemberton (“King Wampum”) gropes a partially undressed Native woman. Franklin, in his trademark bifocals, watches to the right.

James Claypoole, The German bleeds & bears ye Furs (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Claypoole’s engraving serves as a visual counterpart to Hugh Williamson’s pamphlet Plain Dealer. A Quaker man rides a rifle-wielding Scotch-Irish Presbyterian. He is tethered to a tomahawk-clad Indian, who rides a blind-folded German. Benjamin Franklin stands to the left, clutching the Resolves of the Assembly.

Thomas Barton, The Conduct of the Paxton Men (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

The Conduct of the Paxton Men marked a turning point in the pamphlet war. While the pro-Paxton pamphlet was originally published anonymously, it has since been attributed to the prominent Lancaster figure Rev. Thomas Barton, a prominent Anglican missionary from Lancaster. Barton synthesizes the apologist strategies of Declaration and Remonstrance and Apology of the Paxton Volunteers and provides a forceful response to Franklin’s Narrative of the Late Massacres. The pamphlet disparaged the reputation of the Native victims, justified the conduct of the Paxtons using gratuitous scenes of frontier violence, and assailed the motives and pacifist principles of Quaker Assembly members.

1764 Election

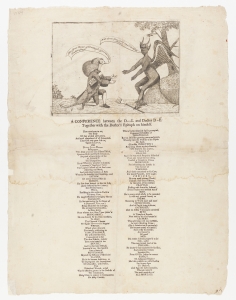

Isaac Hunt, A Conference Between the Devil and Doctor Dove (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Hunt, whom Peter Silver has called a “one-man pamphlet shop during the Paxton crisis,” personalized the Paxton debate. In this cartoon, Hunt depicts Dove in a conference with the devil followed by a satirical epitaph that accuses him of sexual immorality.

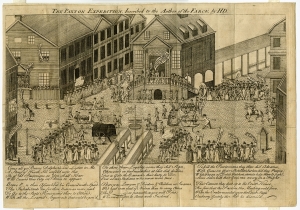

Henry Dawkins, The Paxton Expedition (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Paxton apologist Henry Dawkins takes aim at Quaker militant defense of the Lenape and Moravian Indians. In Dawkins’s illustration, crowds of onlookers, whose plain hats identify them as Quakers, call out in banners suitable to a parade. At the center of the frame is the ringleader, a Friend, who readies a canon. Devoid of the impetus for the confrontation (the Paxton threat to Pennsylvania’s Christianized Indians), Dawkins’s cartoon transforms Philadelphia’s orderly, grid-patterned streets into the stage of a circus.

“The Quakers so peaceable as you will Find:

Who never before, to Arms were Inclined

To kill the Paxtonians they then did Advance,

With Guns on their Shoulders, but how did they Prance.”

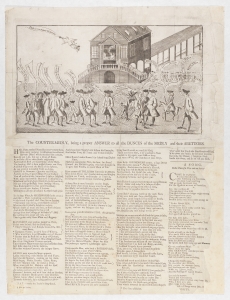

Isaac Hunt, The Election, a Medley (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

In this pro-Franklin cartoon, Isaac Hunt repurposes the plate used in Dove’s The Paxton Expedition to caricature Presbyterians. One remarks, “We Pres[byteria]ns spring up like mushrooms,” while another adds, “and wither as soon.” Hunt embeds Dove (bottom center), accompanied by a black mistress to resurface rumors that he had circulated in Conference.

David James Dove, The Counter-Medley (Philadelphia, 1765). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

In this pro-Paxton cartoon, Dove answers Hunt and assails Franklin by depicting him as an “agent” of the Devil (bottom center). A Paxtonian character on horseback remarks, “March on brave Germantonians,” framing the 1764 election as an electoral equivalent of the Paxton march.

The Unpublished Story

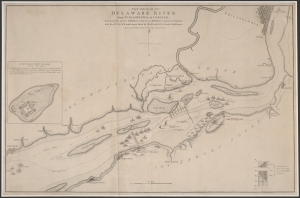

William Faden, The Course of the Delaware River from Philadelphia to Chester (Philadelphia, 1778). Free Library of Philadelphia.

While Paxton critics and apologists assailed one another’s character and debated politics, one hundred forty Lenape and Moravian Indians languished in internment. These individuals were first held at Province Island, where the Philadelphia International Airport is situated today. They likely resided at the “Pest House,” noted in this map.

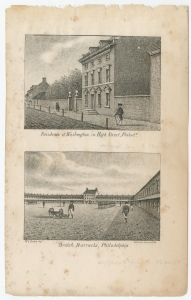

William Breton, Washington Residence and Philadelphia Barracks (Philadelphia, 1830). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

In early-1764, the Lenape and Moravian Indians were relocated to the Philadelphia Barracks in Northern Liberties. That military installation, built to house British troops during the Seven Years’ War, appears in the bottom image of this engraving (“British Barracks, Philadelphia”).

Moravian Missionaries, Diary of the Indians in the Barracks in Philadelphia (Philadelphia, April 2, 1764). Moravian Archives of Bethlehem.

Moravian missionaries visited the Native Peoples interned at Province Island and later the Philadelphia Barracks. These diaries provide a detailed account of more than a year internment marked by illness, death, and near-continual fear and uncertainty.

“We were very worried about our poor Indians because it seemed that no one wants to take care of them anymore. One sees in the writings that are published almost every day the many accusations and great enmity against our Indians; that through [such writings] the people are enticed to be more and more against us, and if our dear Lord does not specifically protect us, then we must still become victims.”

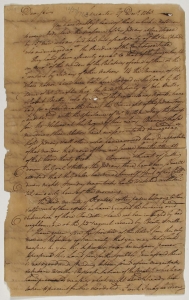

Jacob Whistler, Letter to William Peters (Lancaster, April 9, 1764). Pennsylvania State Archives.

Jacob Whistler, the caretaker of Conestoga Manor, records families settling where the Conestogas resided just three months earlier. Whistler notes that at least one of the families bears relation to the Paxton murderers.

“As I have been appointed to take Care of Indian [Manor] I therefore [acquaint] you that there [are] already two families living on said Land and the third is already a Ploughing there and is Expected to move on said Lands…I have therefore taken some of the [neighbors] as [Evidence] and [warned] them of the Land the answer was that they had Possession and would keep it and would [lose their] Lives before they would be turned [off] the Land they Care for no [Governor], Sheriff, nor any other officer.”

Aftermaths

Mathew Carey, Plat of the Seven Ranges of Townships being Part of the Territory of the United States N.W. of the River Ohio (Philadelphia, 1814). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Mathew Carey’s atlas illustrates how the territories northwest of the Ohio River were incorporated into the United States following the passage of the Northwest Ordinance. That territory was carved out of the trans-Appalachian west, including the very territories contested by the Paxtons.

The Friendly Association, Message to the Delaware Indians (Philadelphia, August 6, 1772). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections.

Upon learning that the Delaware had set out to “settle in a Country very distant,” a Friendly Association writer fondly recollects their longstanding friendship. The letter ends with a promise of money for resettlement.

“Your Friends in Philadelphia often remember the old friendship, which was established between your fathers & ours & hath been maintained between you & us at all times, and even when thick Clouds hung over our heads & it was so dark we could scarce see each other…hold fast the Chain of Friendship.”

Recollections

Benjamin West, Penn’s Treaty with the Indians (Philadelphia, 1771-72). Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

In 1770, Thomas Penn commissioned a painting by Benjamin West to celebrate his father’s participation in the Treaty of Shackamaxon. This famous painting, later recreated by Edward Hicks in his Peaceable Kingdom series, imagines a scene of Native-Colonial harmony that draws a stark contrast to the violence that had unfolded five years earlier.

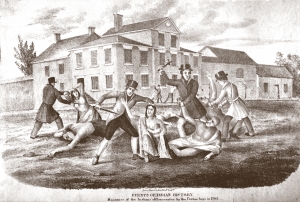

James Wimer, Massacre of the Indians at Lancaster by the Paxton Boys (Lancaster, 1841). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

This nineteenth-century lithograph provides one of the most iconic visual representations of the Paxton massacre at the Lancaster workhouse. While Wimer’s image captures the brutality of the violence, it does take some liberties. For example, the Paxton murderers are shown in formal Victorian attire, including top hats.

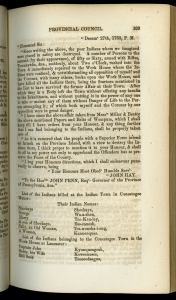

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania (Harrisburg, 1852). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

The Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania contain a detailed account of the massacres, including the Native and English names of victims. These records have been widely available since the mid-nineteenth-century.

![Jacob Taylor, Survey (Lancaster, 1717). Pennsylvania State Archives. Jacob Taylor, Survey (Lancaster, 1717). Pennsylvania State Archives. The map is rendered in ink and depicts the borders of “Conestogoe Mannor, 16000 Acres” [Conestoga Manor] in 1717. The land is somewhat triangular, bordered by the Susquehannah River [Susquehanna] to the west and southwest and the winding Conestogoe Creek [Conestoga] to the east and southeast. Textual notes on the map mark prominent trees along the property line, Indian Town, and three subdivisions within the Manor. Indian Town is also marked by a drawing of twelve small houses. It is situated in the southern part of the Manor, in the center of the map. The largest of the three subdivided plots is vaguely rectangular and situated along the northeast corner of Conestoga Manor. It reads, “Andrew Hamilton 1500 [acres]. Returned into ye Secretary’s office ye 13th [illegible] 1735. By Warr’t [warrant] dated the 10th of the June month.” The two smaller plots are situated on the southern border of the manor between Indian Town and the Conestoga Creek. The western plot reads, “J. C. 500 acres is but 300.” The eastern plot reads, “J. L. 500 acres is 400 acres.” There is a short paragraph at the bottom right corner of the map. It reads, “Isaac Taylor laid out to John Cartlidge 500 [acres] to James Logan 500 [acres] without James’s knowledge or order & w’ch [which] he refused to take. But the Proprieties by their Warr’t [warrant] require a return of 700 [acres] within the 2 tracts to be made into the secretary’s office.”](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/1717-first-map-showing-Indiantown_edited-1-300x295.jpg)

![John Forbes, Letter to Israel Pemberton, (Shippensbourg, August 18, 1758). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections. John Forbes, Letter to Israel Pemberton, (Shippensbourg, August 18, 1758). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections. During the Seven Years' War, Quakers played a central diplomatic role by organizing the Friendly Association, a non-governmental organization that laid the groundwork for the Treaty of Easton in 1758. Friendly Association correspondence reveals the political sensitivity of diplomacy. "I need not tell you that a Jealousy of the Quakers grasping at power, has perhaps taken place in some people's minds; you have now a very critical time of showing that you are actuated only by the [public] good and the preservation of those provinces."](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/HC1122066_01-247x300.jpg)

![Israel Pemberton, Letter to Charles Read (Philadelphia, September 10, 1758). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections. Israel Pemberton, Letter to Charles Read (Philadelphia, September 10, 1758). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections. "[T]he success of the business depends much on setting out right & our Governor has neither inclination nor judgement to act, as ye occasion requires & would I believe pay more regard to a hint from a Brother [Governor] than to either [persuasions] or remonstrances from his Subjects."](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/HC11-22073_01-219x300.jpg)

![John Forbes, Letter to Israel Pemberton (Philadelphia, January 15, 1759). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections. John Forbes, Letter to Israel Pemberton (Philadelphia, January 15, 1759). Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections. "I should be very sorry that you persuaded me to Do any thing that could give Umbrage to the province or provincial Commissioners by giving protections for carrying […] your goods. [Though] I cannot but highly applaud your Zeal for the service."](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/HC11-22114_01-300x219.jpg)

![[James Claypoole], Franklin and the Quakers (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia. [James Claypoole], Franklin and the Quakers (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia. Dealings with the Quakers complicated Benjamin Franklin's political career. Franklin appears in the foreground of this etching, holding a sack labeled "Pennsylvania money." To the left, the prominent Quaker merchant Abel James distributes tomahawks from a barrel labeled "I.P."](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/WatsonsAnnals-Yi2-1069-F-274-300x171.jpg)

![[Anonymous], A Serious Address (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia. [Anonymous], A Serious Address (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia. Published contemporaneously with Narrative of the Late Massacres, this pamphlet provides the first insinuations of Paxton apology. The author complains of "too general Approbation" of the killings, despite their being "contrary to the Laws of Nations." The pamphlet's appearance of impartiality earned it significant popularity – A Serious Address was republished in four editions.](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/am1764ser-795-d-6-p1-208x300.jpg)

![[Anonymous], Petition by the Inhabitants of Lancaster County (Lancaster, 1764). Moravian Archives of Bethlehem. [Anonymous], Petition by the Inhabitants of Lancaster County (Lancaster, 1764). Moravian Archives of Bethlehem. This letter may have served as a draft of the Paxton leaders' Remonstrance. Notably, Petition by the Inhabitants of Lancaster County only raises the problem of representation as a means to raise the concern that settlers might be tried in Philadelphia courts, rather than by their peers in the borderlands](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/INPAF0051-C00000-M0000089-00220-183x300.jpg)

![[Anonymous], Apology of the Paxton Volunteers (Philadelphia, 1764). Historical Society of Pennsylvania. [Anonymous], Apology of the Paxton Volunteers (Philadelphia, 1764). Historical Society of Pennsylvania. This unpublished, anonymous manuscript added visceral depictions of frontier warfare to Smith's account. In place of scenes of violence against the Conestogas (as in Franklin's Narrative of the Late Massacres), the volunteers emphasize the mangled bodies of settlers. Whereas Declaration and Remonstrance advocated for changes in settlement policies, Apology of the Paxton Volunteers sought the vindication of the Paxtons.](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/10766-Am283_04-300x203.jpg)

![Isaac Hunt, The Election, a Medley (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia. Isaac Hunt, The Election, a Medley (Philadelphia, 1764). The Library Company of Philadelphia. In this pro-Franklin cartoon, Isaac Hunt repurposes the plate used in Dove's The Paxton Expedition to caricature Presbyterians. One remarks, "We Pres[byteria]ns spring up like mushrooms," while another adds, "and wither as soon." Hunt embeds Dove (bottom center), accompanied by a black mistress to resurface rumors that he had circulated in Conference.](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/12056-Bc612El25b_1-234x300.jpg)

![Moravian Missionaries, Diary of the Indians in the Barracks in Philadelphia (Philadelphia, April 2, 1764). Moravian Archives of Bethlehem. Moravian Missionaries, Diary of the Indians in the Barracks in Philadelphia (Philadelphia, April 2, 1764). Moravian Archives of Bethlehem. Moravian missionaries visited the Native Peoples interned at Province Island and later the Philadelphia Barracks. These diaries provide a detailed account of more than a year internment marked by illness, death, and near-continual fear and uncertainty. "We were very worried about our poor Indians because it seemed that no one wants to take care of them anymore. One sees in the writings that are published almost every day the many accusations and great enmity against our Indians; that through [such writings] the people are enticed to be more and more against us, and if our dear Lord does not specifically protect us, then we must still become victims."](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/MissInd_127_2-20-244x300.jpg)

![Jacob Whistler, Letter to William Peters (Lancaster, April 9, 1764). Pennsylvania State Archives. Jacob Whistler, Letter to William Peters (Lancaster, April 9, 1764). Pennsylvania State Archives. Jacob Whistler, the caretaker of Conestoga Manor, records families settling where the Conestogas resided just three months earlier. Whistler notes that at least one of the families bears relation to the Paxton murderers. "As I have been appointed to take Care of Indian [Manor] I therefore [acquaint] you that there [are] already two families living on said Land and the third is already a Ploughing there and is Expected to move on said Lands…I have therefore taken some of the [neighbors] as [Evidence] and [warned] them of the Land the answer was that they had Possession and would keep it and would [lose their] Lives before they would be turned [off] the Land they Care for no [Governor], Sheriff, nor any other officer."](https://ghostriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/r017_0320_Box001_0000_LetterToWilliamPetersFromJacobWhisler_17640409_02-184x300.jpg)